Border cities' relationship thrives amid economic woes, negative rhetoric

By Julia Tylor and Mauro Whiteman

As the first streaks of sunset sweep across the sky over Nogales, Ariz., a trio of girls shuffle alongside the fence that reaches high above their heads. They peer anxiously through the gaps in the bars as they walk until, finally, they glimpse a woman walking toward them on the other side of the border.

“Mama,” one of the girls cries, shattering the twilight silence.

They rush to meet her, leaning as close as they can to the barrier, choosing a spot where they can see her face through the steel rods.

I’ll meet you at the crossing, she tells them in Spanish.

This is the spirit of Ambos Nogales — both Nogales — a single community that spans two nations. Divided by a border that has seen an increase in law-enforcement presence over the years and pummeled by the economic decline in the U.S., the twin cities have undergone changes in their relationship over the years.

But despite recent tensions stemming from controversial legislation and complaints of long waits at border crossings due to understaffing, the intertwining roots of Ambos Nogales run too deep to be destroyed by politics or economic woes.

Two cities, one communityWhen Allison Moore talks about Nogales, Ariz., her expression grows wistful.

“It was the best little place to live,” she says. “It never crosses your mind that it’s going to be a problem.”

Moore, who works as the communications director for the Fresh Produce Association of the Americas in Nogales, used to live one block north of the U.S.-Mexico border. Her community, she says, spanned the dividing line.

Like others living in the borderlands, Moore saw the area go through continual changes. The most recent was an upgrade to the fence: Last summer, the wall made of sheet metal was torn down and replaced by a fence made of steel beams and grounded in concrete.

In many ways, the demographics of Nogales, Ariz., are more in line with those of Mexico than the U.S. According to the 2010 U.S. census, 95 percent of the population in Nogales, Ariz., is of Hispanic or Latino origin, compared with 3.9 percent of non-Hispanic whites. This ratio is in stark contrast to Arizona as a whole, where people of Hispanic or Latino origin compose 29.6 percent of the population, compared with 57.8 percent of non-Hispanic whites.

The two cities are also relatively similar in appearance; the border fence runs through a community that looks and feels like one city instead of two.

Bruce Bracker, a member of the Nogales Port Authority who owns Bracker’s Department Store in downtown Nogales, tells the story of how, in the 1970s, the two cities would hold a Cinco de Mayo parade that began in Mexico and ended in the U.S.

“That’s really the feeling of our community,” he said. “We have friends and family on either side of the border.”

Olivia Ainza-Kramer, president of the Nogales-Santa Cruz County Chamber of Commerce Visitor & Tourism Center, was born in Nogales, Ariz., and grew up believing that the houses across the border were just as much a part of her neighborhood as the houses next door.

“Whenever we had a celebration either in Mexico or here in Arizona, we used to cross, used to celebrate either in Mexico or over here,” she said. “And we miss those times, because it was more like a family. Ambos Nogales — Nogales, Sonora, and Nogales, Arizona — we don’t see each other as another country, another city. No, we see it as a family. Because this is Ambos Nogales.”

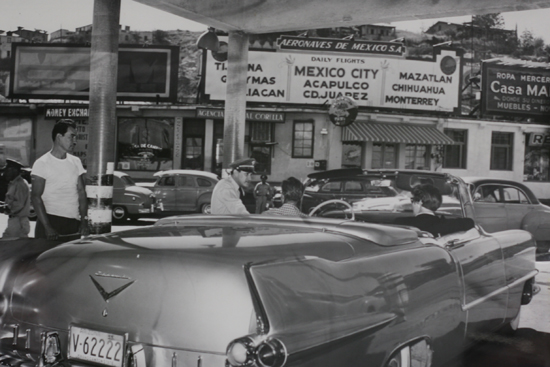

The changing face of the borderIn years past, all that divided the U.S. and Mexico in many places was a yellow line painted on the asphalt. Border security was an honor system of sorts. Ambos Nogales were twin cities tightly intertwined. Thriving trade created a symbiotic relationship between Nogales, Ariz., and Nogales, Sonora. Officials on both sides of the border viewed the lack of a physical barrier as a symbol of pride.

Eventually, however, a patchwork of barbed-wire and chain-link fences sprung up across parts of the borderlands. Ambos Nogales was split by “la línea” – the line – a chain-link fence riddled with gaps that both Americans and Mexicans would pass through to frequent shops or eateries on the other side of the border.

In 1994, the chain-link fence was replaced by an opaque wall made from repurposed military landing mats – “corrugated slabs that (were) always being repaired,” Moore recalls.

Then, last year, the rusting wall was demolished. The borderline was taken over by 2.8 miles of bollard fencing, reinforced steel pipes jutting up from the ground, reaching as high as 30 feet in some areas. The bars are closely spaced so that the fence can be seen through but not slipped through.

Agent Crystal Amarillas of the Border Patrol’s Tucson Sector, which includes Nogales, said the bollard fencing has been an improvement over the landing-mat fencing because it is higher and stronger – and therefore harder to jump over or break through.

“The (old) fence was lower, weaker,” Amarillas said. “It was getting cut. ... We’d get it fixed, and in a matter of hours, they’d cut it again.”

Moore said the bollard fencing has been a boon to the community because it is more secure yet less imposing than the landing-mat fence.

“You can see the rest of your community,” she said. “You can see the stores and the streets and the traffic and the people. It’s not some other place on the side of the wall. I think psychologically, if you were to do a study, I think you’d find people feel more connected being able to see through it.”

The bollard fence, at 18 to 30 feet, is taller than the old landing-mat fence, which stood only eight to 12 feet tall.

Moore said although the bollard fence is taller, the fact that it can be seen through does a better job of fostering a sense of community than its predecessor, which comprised solid metal slabs.

“Even if it were taller, I would never know that just glancing at it,” she said.

Waiting in lineThe number of vehicle passengers and pedestrians crossing the border into Nogales, Ariz., has steadily declined since 2007, as has the number of vehicle crossings, according to the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Bureau of Transportation Statistics.

In 2011, 8,978,726 pedestrians and passengers crossed into Nogales, Ariz., a 46 percent decline from 16,534,118 in 2007. A total of 2,938,012 vehicles -- passenger vehicles, trains, trucks and buses -- crossed in 2011. This was a 16 percent decrease from 2007, which saw 3,488,778 vehicle crossings.

In terms of human crossings, foot traffic had the bigger decrease between 2007 and 2011: 54 percent, compared with a 38 percent decrease in visitors crossing in vehicles.

Perceptions of the crossing trends are divided in Nogales. Despite the numbers, Customs and Border Protection agents report a slight increase in crossings through the Nogales ports of entry, adding that the trends are difficult to pin down because different agencies report different numbers. Meanwhile, some business owners, including Bracker, say they have seen a decline in both crossings and downtown business in recent years.

Bracker said his business has suffered due to a drop in crossings brought on by increasingly long wait times at the ports of entry.

He likened the wait for Mexican tourists at the land ports to standing in a checkout line at a store. If the line is too long, he said, they decide not to cross into Arizona to shop.

“We make our buying decisions based on how long we like to wait in line,” he said.

Bracker blames the long wait times on understaffing of Customs and Border Protection agents at the ports of entry and a dearth of badly needed upgrades to the ports in order to accommodate more traffic.

“On any given day, you can walk out here, and you can see that 50 percent of the infrastructure is closed because we don’t have enough manpower,” he said. “All of this relates to wait time.”

The Mariposa Land Port, located on the border between both cities of Nogales, is the third-busiest land port of entry in the nation, according to the U.S. General Services Administration. An ongoing, $184 million project funded by the GSA’s American Recovery and Reinvestment Act is an effort to modernize the port, bringing it up to speed with increases in traffic flow.

The 216,000-square-foot project, which broke ground in October 2009 and is slated for completion in spring 2014, will expand the number of travel lanes at the Mariposa port of entry from four to 12, according to Customs and Border Protection spokeswoman Edith Serrano.

Ambos Nogales boasts three ports of entry; in addition to the Mariposa Land Port that joins the west side of the cities, downtown Nogales, Ariz., is joined with Mexico by the DeConcini Port of Entry and its pedestrian-only counterpart, the Morley Gate.

Juan Osorio, Customs and Border Protection spokesman for the port of Nogales, Ariz., works at the DeConcini port. The wait time at the downtown port, he said, is between 25 and 90 minutes on average in a car, although the wait time climbs during holidays such as Thanksgiving and Christmas. Crossing on foot tends to be faster, but the wait in the pedestrian lane can be up to an hour long, he said.

“The majority of the people that cross through here are pedestrians,” Osorio said. “It’s so much easier to walk through, make your purchases and walk back.”

Osorio said CBP saw a decline in crossing numbers a couple of years ago — a byproduct of the economic downturn. But he said the overall trend has been positive.

“Our numbers are going up every year,” he said.

Serrano said CBP has seen a slight increase in the number of travelers it has processed in Nogales, but she said the varying perspectives on crossing numbers result from different methods of measuring the numbers.

“To me, it’s speculation because we don’t really know all the factors,” she said.

She said while the length of the lines at the ports of entry do affect whether Mexican visitors decide to cross, the quality of U.S. products draws many over to shop.

“They kind of monitor the lines; if the lines aren’t too long, they cross,” she said. “It’s convenient for them. The products here are better than what you see in Mexico.”

New crossing requirementsIn 2009, U.S. Customs and Border Protection implemented a new plan to help expedite the process of crossing the border. The Western Hemisphere Travel Initiative requires that U.S. citizens over the age of 16 present either a U.S. passport, a passport card, an enhanced driver’s license or a trusted-traveler program card, according to the CBP website.

Trusted-traveler programs include FAST for trade shipments between the U.S. and Canada or Mexico, NEXUS for travel between the U.S. and Canada, and SENTRI for travel between the U.S. and Mexico.

The Secure Electronic Network for Travelers Rapid Inspection program started in 1995 in California and has since expanded to the nine largest ports of entry along the U.S.-Mexico border, including in Nogales, according to a CBP fact sheet.

Serrano, who is stationed in Tucson but frequently visits the Nogales ports of entry, is enrolled in the SENTRI program. She said she has seen travelers cross the border multiple times per day using SENTRI cards. Some parents from Mexico travel across the border to drop off kids at school and then return to pick them up, she said.

The SENTRI pass costs $122.25 per person and is good for five years, according to the CBP website. Osorio said the enrollment is online, and, once accepted, travelers can use designated commuter lanes that have shorter wait times due to speedier document inspections.

But long before the Western Hemisphere Travel Initiative went into effect, border crossings were a simpler matter, according to Yvonne Delgadillo. Delgadillo is president of the Nogales Community Development Corp. and was born and raised in Nogales, Ariz.

“When I was growing up here ... Nogales, Arizona, and Nogales, Sonora, was pretty much one single community,” she said. “You would cross on a daily basis or perhaps on a weekly basis however many times without having to worry about having any paperwork with you, without being harassed about one thing or the other. All you would have to do is declare your citizenship, and you were free to go.”

The single community that spanned the dividing border has been hampered by new document requirements, Delgadillo said, but post-9/11 worries and increased politicization of border security may have laid the past to rest permanently.

“For us, it was just crossing back and forth, and it really wasn’t an issue because it was something we were used to. But now that you’re required to have a passport … there’s just a lot of other obstacles that have come in,” Delgadillo said.

But Delgadillo does not believe the new restrictions are solely to blame for decreased traffic between the two sides of Ambos Nogales. Negative publicity about border communities, restrictions on crossing for both Mexican and American citizens, and economic issues in the U.S. have all contributed to the slump in border crossings.

During the week of Thanksgiving, streets in downtown Nogales were lined with shoppers in search of good deals, but this influx of visitors is mostly common around the holidays — an exception, not the rule.

“I remember when I was young, downtown used to be a very vibrant place to do business. You would go downtown and you couldn’t find parking sometimes,” Delgadillo said, contrasting the past with the current state of downtown Nogales. “Sometimes, when you go downtown, it almost seems like it’s a ghost town. You can find great products, and there’s still a lot of opportunity there, but the people aren’t there anymore.”

Not a war zone“Drug and human smuggling, home invasions, murder —” begins a 2010 political advertisement by Sen. John McCain. The 30-second commercial, shot in Nogales, Ariz., would become famous for its tagline — “Complete the danged fence,” McCain tells Pinal County Sheriff Paul Babeu — but the message goes deeper than its call for additional border security.

Public perception of Nogales, Ariz., from the outside has been overwhelmingly negative, hurting area businesses and diminishing U.S. tourism, said Ainza-Kramer of the Nogales-Santa Cruz County Chamber of Commerce Visitor & Tourism Center.

“If we were a little bit more positive, we could create a lot of stories that would make a huge impact in the community,” she said.

But the story of safety and security in Nogales, Ariz., often goes untold, lost in the flood of negative media coverage along the U.S.-Mexico border.

According to the 2010 U.S. census, the total population of Nogales, Ariz., is 20,837. Of that number, about 2,000 are law-enforcement agents, said Nils Urman, a founding board member of the Nogales Community Development Corp.

The high density of law-enforcement officers, from police officers to Border Patrol agents, makes Nogales one of the safest cities in Arizona, according to Moore of the Fresh Produce Association of the Americas.

“If you compare us per capita to someplace like Phoenix, we would have massive movement from Phoenix to here if people understood the statistics,” Moore said.

The disconnect about safety in U.S. border cities is not specific to Arizona. El Paso, Texas, which shares its border with sister city Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua, Mexico, has topped the rankings as the safest city in the U.S., and yet it has been unable to shake its war-torn image.

Nogales, Ariz., faces a similar struggle.

“My family back from Virginia, every time they read the news, they think I’m inside of some war zone. ... And it’s like, we’re not hiding in bunkers behind sandbags here,” Moore said.

Even within Arizona, a stigma has been placed on cities that lie on the border, Delgadillo said.

“You have a lot of perceptions (from) Arizonans themselves who have lived here all their life and are terrified of coming to the border. They think we’re very unsafe, which is totally a misconception,” she said. “So despite the safety that we can rely on here, we don’t see the activity that we used to see.”

Ainza-Kramer believes that each visitor to the twin cities of Ambos Nogales can be an ambassador and help fight off the negative perception.

“These borders are more secure than anywhere in the United States because of the law presence that we have here,” she said.

A political symbol and local prideIllegal immigration has become a hot topic for U.S. politicians, who make claims about the need for an electric border fence or law-enforcement agencies finding beheaded bodies in Arizonan deserts. But often missing from the discourse is any mention of the actual community that knows firsthand the “border situation” -- as it is cordially referred to in government documents and news articles.

“You have a lot of politicians talking about the border, and yet they’ve only been here for all of five minutes and have no notion of what it is or what this community is all about,” Delgadillo said.

While both Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama have recognized that border security is incomplete without immigration reform, the fence has become a political symbol of the war against illegal immigration.

For those living on the border, it begins to feel like external forces are trying to divide the community.

“To be honest with you, regardless of how many fences you put up there, it’s not addressing the real issue,” Delgadillo said. “A lot of people look at it here as it’s just another Berlin Wall type of metaphor.

“It’s really the symbolic things, and it’s looking at immigration or the line or the fence … in one single view, as opposed to seeing the big picture. Whereas here, we live it and breathe it. We rely on them, they rely on us,” she said.

Interdependence and local pride have been tools with which the community of Ambos Nogales has dealt with an increasingly hostile political environment. Despite Arizona’s controversial immigration law and a slow-to-recover economy, residents of Nogales have hope for its future.

“There are definitely a lot of opportunities for Nogales, and it’s a matter of grabbing onto those opportunities, whether its people coming here to go shopping, driving new businesses here ... those are opportunities that we have,” Moore said.

The time frame for achieving this opportunity depends on how quickly Nogales, Ariz., can overcome its image problem.

“I do see a lot of potential here in Nogales,” Delgadillo said. “I just wish that others would see the same potential.”